The Curious Adventures of Cabeza de Vaca

By | July 4, 2019

The circuitous travels of a shipwrecked conquistador have passed on to us the most detailed information of the peoples who lived in the southeast and southwest of North America before the European conquest. In the process, he was transformed from conquistador to an advocate of Indian rights.

In April 1528, the Spanish conquistador, Pánfilo de Narváez landed an expedition of 300 men near modern-day Tampa Bay, Florida. They set off into the interior to ruthlessly search for gold but instead found only disease, hostile natives, starvation, and ultimately death. By September, only 60 men remained alive. These would-be conquerors decided to craft boats to sail west to New Spain (modern-day Mexico), melting down their own equipment so that they could escape. But the boats were swept out to sea by the powerful current of the Mississippi River. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, the treasurer and Chief Constable of the expedition, commanded one of the boats. He was shipwrecked on Galveston or some other island off the coast of Texas with fifty men. By the spring of 1529, only fifteen of these survived.

The Indians brought de Vaca and his men into their lodges, fed them, and clothed them. But the Spaniards were frightened, thinking that they were going to be sacrificed at any time. Instead, in a complete role reversal, the Indians enslaved the Spaniards.

These were hard times. Diets were spare and monotonous even for the Indians. Many of the Spaniards, who were separated among tribes, began to succumb to starvation. Meanwhile, de Vaca started going native. He learned six native tongues and carefully observed their behaviors and customs as if it is the first time he looking at them. These observations, which he recorded later, crafted the first ethnography of the native tribes of the Gulf Coast providing information. Considering the fact that many of those tribes were gone upon the arrival of other Europeans, probably due to disease that de Vaca and other conquistadors carried, its value as a historical document is beyond measure.

After a time of enslavement in which he and others were passed from tribe to tribe, de Vaca escaped to another tribe of Indians.

Eventually, the strangeness of de Vaca to the Indians prompted them to tell him “to be useful” and cure the sick. Although de Vaca and the other Spaniards at first refused, pragmatism won out when they were threatened with starvation. By de Vaca’s account, they imitated the way in which Indian shamans healed, by breathing on the wound, but as an added flourish, de Vaca made the sign of the cross and recited prayers. This apparently had a good rate of success, making de Vaca one of history’s first faith healers.

De Vaca eventually became a sort of itinerant trader. Because the local Indians were in a constant state of warfare, de Vaca proved to be a reliable, neutral third party. His goods consisted mainly of “seashells and cockles.”

During this time, de Vaca was shocked to learn that five other Spaniards had become cannibals. De Vaca noted that the Native Americans had the same reaction as the Europeans, “The Indians were quite upset by this happening and were so shocked that they would have killed the men had they seen them begin to do this.”

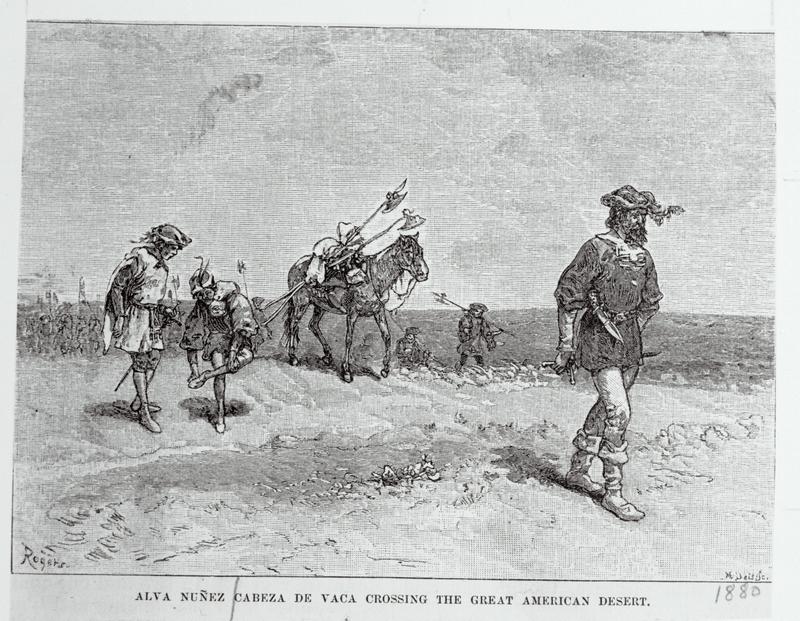

By 1532, de Vaca’s fifteen men had been reduced to four: de Vaca himself, Alonzo del Castillo Maldonado, Andres Dorante, and a black slave from North Africa named Estevanico. Deciding to risk a dangerous journey, they headed west overland in hopes of reaching New Spain.

It is not entirely clear the exact route de Vaca and his companions followed, but they certainly crossed into Texas and maybe New Mexico and Arizona before coming to the northern territories of New Spain. In doing so, they were the first non-native Americans to journey into those regions. As they progressed through these lands, de Vaca took to trading his purported healing powers for safe passage. In fact, according to de Vaca, word of their coming inspired warring tribes to make peace. He also came to believe that the reasons for his travails were to convert the Native Americans to Christianity.

In July 1536, in Culiacán in present-day Sinaloa, they encountered Spanish slave-takers. They were astonished to see de Vaca, especially since he was dressed entirely as a native. It took some time for them to readjust. De Vaca wrote, “for many days I could bear no clothing, nor could we sleep, except on the bare floor.”

In 1537, Cabeza de Vaca returned to Spain where he memorialized his journey in La relación of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. His account shows sympathy for the Indians and he was horrified that the Spanish enslaved and hunted the Indians. For the rest of his life, he was a strong supporter of Indian rights. He begged the King of Spain to make the Indians “...become willingly and sincerely subjects of the true Lord Who created and redeemed them. We believe they will be, and that Your Majesty is destined to bring it about, as it will not be at all difficult.”

So even though de Vaca supported the Native Americans, at his core he still upheld the right of Spain to control Indian groups, especially with the express purpose of converting them to Christianity. Still, the story of de Vaca is an amazing one of self-discovery.