New Year’s Resolutions, A History Of Broken Promises

By | December 5, 2019

While breaking promises is generally considered a bad thing, there is one time of year when millions of people make promises - to themselves, their family, God, or maybe just the universe at large - only to break them soon after. That time of year is New Year’s Day and these promises are collectively referred to as New Year’s resolutions. The tradition of making life-altering proclamations at the start of the new year is one that dates back approximately four thousand years.

The ancient Babylonians are believed to have been the first civilization to celebrate the new year; however, their year began with the spring equinox, which would have been around mid-March and coincided with the planting of crops. Their celebration consisted of a twelve-day festival known as Akitu during which their king would either be reaffirmed or replaced. Part of the celebration also involved making promises to the gods. Typical promises included repaying debts or returning borrowed items. They believed the gods would reward them with good fortune for keeping these promises.

While the Babylonian new year was linked to the spring equinox, the ancient Egyptians began their year with the annual flooding of the Nile, which occurred at the beginning of July and renewed the land’s fertility. During this time, the Egyptians would make sacrifices to Hapi, the god of the Nile. They believed Hapi would reward them for their sacrifices with good fortune and bountiful harvests, as well as increasing the success of their militaries.

Sometime around 46 B.C., Julius Caesar of ancient Rome made January 1 the start of the new year. Previously, the Roman year had consisted of ten months, and as the Babylonian year, beginning with the spring equinox. However, there were about sixty days in winter that were not included in any of the named months. This was changed around 700 B.C. when two more months were added, but it was Julius Caesar’s new calendar which changed the beginning of the year to coincide with the term rotations of newly elected consuls. This was the first time that a calendar was based on civic concerns rather than agricultural ones.

The month of January was named for Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings. Janus was believed to have two faces, giving him the ability to simultaneously look ahead to the future and backward into the past. Just as the Egyptians did with Hapi, the Romans offered sacrifices, as well as promises of future good conduct, in exchange for good fortune. For early Christians, New Year’s Day was set aside to contemplate past mistakes and plan for a better future. Prayer vigils were commonly held. In the Middle Ages, knights were known to take “The Vow of the Peacock” in which they would place their hands on a peacock as they renewed their chivalric oath.

In 1740, John Wesley, the English clergyman who founded Methodism, created the Covenant Renewal Service, also known as a watch night service, which included scripture readings and worship. These services, which are still celebrated among many Protestant churches, are held on New Year’s Eve or New Year’s Day and provide a Christian alternative to the more hedonistic celebrations found in secular circles. Resolutions for the new year are also frequently a part of these watch night services.

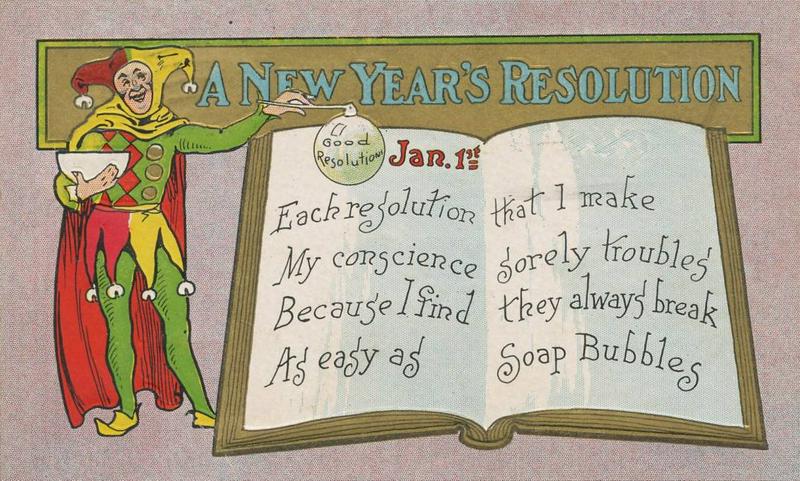

The phrase “New Year’s resolutions” did not appear in print until 1813, in a Boston newspaper. By that time, the tradition had become mostly secular and the nature of the resolutions had become egocentric, with goals of self-improvement (lose weight, stop smoking, etc.) rather than a commitment to moral values. That change and the resulting loss of accountability through divine reward or retribution, is most likely the reason modern New Year’s resolutions have a negligible success rate - of the approximately forty-five percent of Americans who make resolutions, only about eight percent follow through with them. That’s a lot of broken promises.