Mummification and Burial Practices of Ancient Egypt

By | March 8, 2019

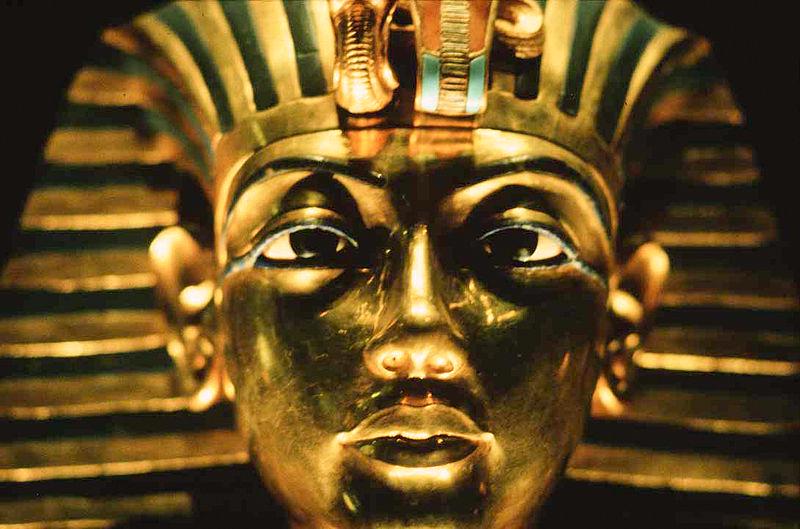

King Tut Ankh Amun Golden Mask. Source: (commons.wikimedia.org)

An early form of embalming, mummification began in ancient Egypt circa 3500 B.C. It later spread to other civilizations including Incan, Australian aboriginal, Aztec, African, and others. While the specific rituals varied by culture, the purpose remained the same: to honor the dead and preserve their bodies.

The idea for mummifying the dead is thought to have evolved from the manner in which corpses were preserved in the dry sand during the Badarian Period. These corpses were not mummified but rather buried in shallow, rectangular or oval graves. Over time, the graves were replaced by the mastaba tomb, which was considered to be a place of transformation where the soul would move on to the afterlife. The Egyptians believed that the soul could not move on unless the body remained intact and it was for this reason that they needed a way to preserve the dead.

Irethorru, keeper of the temple of Amon, giving presents to Osiris, Isis and the four sons of Horus. Source: (commons.wikimedia.org)

Egyptian beliefs regarding the afterlife have their origins in the myth of Osiris. According to the myth, Osiris and his wife, Isis, were the first rulers of Egypt. But Osiris’s brother, Set, was jealous and killed him, cutting up his body and scattering it all over Egypt. Isis put him back together and brought him back to life, but she was unable to retrieve all of his body parts thus he was incomplete and unable to rule on earth. Instead, he became Lord of the Dead in the underworld. Osiris became a symbol of death and resurrection, often depicted as a mummified ruler.

Book of the Dead fragment. Source: (wikiwand.com)

The Egyptians believed the soul consisted of nine parts: the physical body (Khat), the astral self (Ka), the shadow self (Shuyet), the immortal self (Akh), two aspects of the Akh (Sahu and Sechem), a bird aspect with the head of a human (Ba), the secret name (Ren), and the heart (Ab). These parts would be released after death, but without the Khat would be unable to function properly as it needed a familiar form to recognize itself.

Mummification tools. Source: (commons.wikimedia.org)

Egyptian embalmers offered three types of services and it was up to the family of the deceased which one would be performed. Families generally chose the best service they could afford because choosing a less expensive service than they afford might result in their loved one haunting them. In the most expensive service, all the organs were removed and the body was filled with aromatic substances, placed it in a salt mixture called natron, and left covered for seventy days. Afterward, the body would be wrapped in cloth and returned to the family for burial. Less expensive services were less detailed but still involved removing organs, with the exception of the heart, and placing the body in natron.

Bristol Museum Egyptian sarcophagi. Source: (commons.wikimedia.org)

Once the body was returned to the family, the next step was to place it into a coffin or sarcophagus. The body was wrapped in cloth, referred to as the “linen of yesterday” due to the fact that poor families often used their old clothing to wrap the body. Funeral services were public events and often included professional mourners, women called “the Kites of Nephthys” who would encourage the funeral guests to express their grief. Tombs were filled with items the deceased might need in the afterlife, including shabti dolls which could supposedly be brought to life to perform tasks for the deceased. The final act would be to perform the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony, during which the priest would restore use of the eyes, ears, mouth, and nose to the deceased. Afterward, the corpse would be enclosed in the sarcophagus or coffin and buried in a grave or tomb where they would begin their journey to the afterlife.